On May 24th, the Coalition for a Prosperous America released a new working paper, “Job Quality Index for Black, Hispanic and Asian American workers. In this working paper, Jeff Ferry, CPA Chief Economist, and Amanda Mayoral, CPA Economist, present Job Quality Indexes for three important minority groups within the U.S. workforce: Asian, Black, and Hispanic Americans.

In November 2019, CPA published the first U.S. Private Sector Job Quality Index (JQI) report in partnership with Cornell Law School, The JQI “measures the quality of U.S. jobs as distinct from their quantity” using Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data to calculate the average weekly wage for all Production and Nonsupervisory (P&NS) employees. These workers “make up 80% of the total U.S private sector workforce, 98 million out of a total 122 million workers.”

“The JQI is the ratio of high-quality jobs to low-quality jobs, multiplied by 100 and expressed as an index. By calculating the national average weekly wage for all P&NS employees, we can establish a threshold to split high- and low-quality jobs. The jobs in all sectors delivering a weekly wage above the threshold are termed high quality and all jobs below the threshold are low quality. The average weekly wage, or threshold, as of December 2020 was $857.60.”

Since its inception, the “JQI shows that the U.S. creates millions more low-quality jobs than high-quality jobs each year. The JQI for December 2020 was 80.5, indicating that 55% of nonsupervisory workers worked in low-quality jobs, and only 45% in high-quality.”

The results of the new working paper “show that Black and Hispanic American Job Quality Indexes are far below that for the total U.S. population. Asian American JQI however is substantially higher than the overall U.S. JQI. The key findings were:

- “Black American job quality is far worse than that of the total population. The Black Job Quality Index (JQI) for 2020 was 38.7, more than 40 points below the JQI for the total U.S. private sector production and nonsupervisory workforce. For the Black nonsupervisory workforce, 72% of their jobs are low quality, and only 28% rank as high-quality…”

- The JQI for Hispanic Americans was 38.1 in 2020, 42 points below the U.S. JQI. In 2002, 28% of Hispanic American employees held high-quality jobs and 72% were in low-quality employment. Although far below the U.S. JQI, the Hispanic American JQI rose by 29% since 2007, when it was just 29.5. The increase in the Hispanic American JQI was driven largely by the growth of Hispanic jobs in high-quality health care and construction service jobs.

- The Asian American JQI began the period well above the total U.S. figure and rose further, to reach 158.3 in 2020. At that level, 61% of Asian American employees were in high-quality jobs, with just 29% in low-quality. The high and rising Asian American JQI was driven by high-quality professional business service, health care, and finance/insurance jobs.

Ferry and Mayoral offered the following opinion: “Despite rising incomes for many Americans since 2007, Black Americans are not getting their fair share. Job growth for Black Americans since 2007 has been concentrated in low-quality jobs, notably in service sector jobs such as food service and social assistance. The slow growth in high-quality jobs since 2007, including a decline in many manufacturing sectors, has made it more difficult for Black and Hispanic Americans to gain access to these jobs. The JQIs for Black and Hispanic Americans reflect the economic inequality faced by these groups.”

They added, “The changing composition of the U.S. workforce in the years since 2000 hits Black Americans harder than it hits other ethnic groups, in particular whites, because Black Americans are more strongly concentrated among the 64% of the U.S. workforce that does not have a four-year college degree. For workers without four-year degrees, the traditional route to a middle-class income has been the manufacturing sector. That sector’s abrupt decline, which began in the 1980s but accelerated after 2000, has forced these workers to look elsewhere for employment. Unfortunately, the service sectors where jobs have grown most rapidly in this century pay well below manufacturing wages.”

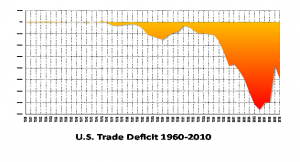

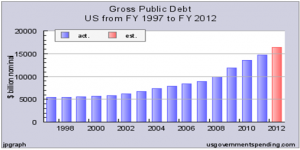

It wasn’t “systemic racism” that caused the loss of higher paying manufacturing jobs —it was the greed of large American corporations with multinational presence that wanted to increase profits by shifting manufacturing to cheaper labor countries reduce costs of regulations. Manufacturing was first shifted to Mexico after NAFTA and then to China after China was allowed into the World Trade Organization in the year 2000 and tariffs were reduced or eliminated. The loss of manufacturing jobs was made worse by China’s flooding the U.S. with cheap imports that put domestic manufacturers out of business.

The loss of high paying manufacturing jobs in cities like Detroit, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh, all cities with high Black populations, turned these cities and others into “job deserts” for high paying jobs.

When I visited Cincinnati in 2016 as the guest of Source Cincinnati, I learned that the city had lost 67% of its manufacturing base, and they were implementing a multi-pronged approach to reviving manufacturing jobs. Some cities in the southern states of North and South Carolina lost nearly all of their textile and furniture manufacturers. In 2017, I saw evidence of this devastation when I visited Greensboro, Raleigh, and High Point in North Carolina and Charleston, South Carolina.

Even in my long-time home of San Diego County, I documented the loss of 185 companies out of my database of about 1,000 manufacturers between 2001 and 2010. I wrote periodic reports starting in 2003, which led me to write my first book, Can American Manufacturing be Saved” Why we should and how we can” published in 2009. This edition and the 2012 edition described the ramifications of losing 5.8 million manufacturing jobs in the U.S. between 2001 – 2010 and made recommendations on how to save American manufacturing.

In conclusion, Ferry and Mayoral recommended: “Policy initiatives to address the inequality of Black and Hispanic Americans suffering from much lower job quality than the total American population include supporting high-wage industries, notably manufacturing. These industries offer the best opportunity for Black and Hispanic Americans, who have relatively less educational qualifications than other Americans, to find high-quality jobs capable of supporting middle class lifestyles.”

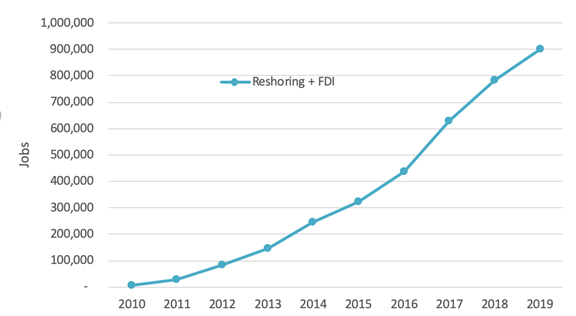

Addressing the problem of rebuilding American manufacturing to create more high paying jobs for all Americans, including Black and Hispanic workers, is the whole focus of my book, Rebuild Manufacturing – the key to American Prosperity published in 2017. Reshoring manufacturing to America and personal decisions by consumers to buy Made in USA products are just two of the simpler ways we can rebuild American manufacturing.