The recently-released U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission report states that is has been ten years since China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO), and “the concerns that originally surrounded China’s accession to the WTO—that China’s blend of capitalism and state-directed economic control conflict with the organization’s free market principles—have proven to be prophetic.” What have been the consequences of China’s accession to the WTO and what are the implications for the future?

At that time, China did not meet all of the traditional requirements for accession, but the WTO took a calculated gamble that China could effectuate the reforms necessary to conform to those requirements within a reasonable period of time. The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission was established by the United States Congress in part to monitor the outcome of that gamble.

Ten years later, it’s obvious from the reports that the WTO lost the gamble. The recent Commission reports that China’s state-directed financial system and industrial policy continues to contribute to trade imbalances, asset bubbles, misallocation of capital, and dangerous inflationary pressures…China’s adherence to WTO commitments remains spotty despite the decade that the country’s rulers were given to adjust.” As a result, these circumstances create an uneven playing field for China’s trading partners and threaten to deprive other WTO signatories of the benefit of their bargain. This is an understatement of the effect on the economy of China’s main trading partner ? the United States.

Chapter one analyzes these issues, beginning with an examination of U.S.-China trading and financial relations and concluding with an evaluation of China’s role in the WTO. It also examined the implications of China’s being relieved of its burden of facing an annual review by the WTO of its compliance due to the fact that the ten-year probationary period ends this year

U.S.-China Trading Relations

For the first eight months of 2011, China’s goods exports to the United States were $255.4 billion, while U.S. goods exports to China were $66.1 billion, yielding a U.S. deficit of $189.3 billion. This represents an increase of nine percent over the same period in 2010 ($119.4 billion). During this period China exported four dollars’ worth of goods to the United States for each dollar in imports China accepted from the United States. In 2010, the United States shipped just seven percent of its total exports of goods to China; China shipped 23 percent of its total goods exports to the United States.

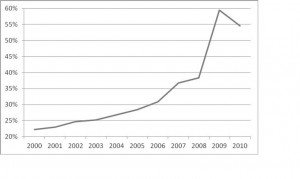

In the ten years since China joined the WTO, the U.S. trade deficit with China has grown by 330 percent. This trade deficit is not explained by a broader trend of American dependence on imports. In the first eight months of 2011, Chinese goods accounted for 20 percent of U.S. imports, while U.S. goods accounted for only five percent of Chinese imports. China’s portion of America’s trade deficit has nearly tripled ? from 22 percent in 2000 to 60 percent in 2009 and 55 percent in 2010 – while the overall U.S. trade deficit with the world has grown from $376.7 billion in 2000 to $500 billion in 2010.

China’s Share of the U.S. Global Trade Deficit (by percentage), 2000–2010

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Trade in Goods and Services (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, August 15, 2011).

The Commission states “These data suggest that the growth in the U.S. global trade deficit reflects growth in the U.S. trade deficit with China and that other emerging economies are being replaced by China as a final supplier of finished exports to the United States.” Of more serious concern is not the size of the U.S. trade deficit with China but the composition of goods. Chinese manufacturing has undergone a dramatic restructuring during the last ten years, away from labor-intensive goods toward investment-intensive goods. Production now is driven less by low-cost labor and more by low-cost capital, which is being used to build next-generation manufacturing facilities and to produce advanced technology products for export. This is demonstrated by the decrease in Chinese exports of labor-intensive products, such as clothing, footwear, furniture, and travel goods as a percentage of total exports. In 2000, exports of these labor-intensive products constituted 37 percent of all Chinese exports. By 2010, this percentage had fallen to just 14 percent.

It’s apparent that this shift has serious implications for the U.S. economy. When China joined the WTO, the United States had already lost production of low-value-added, low-wage-producing commodities such as clothing and toys. But America’s export strength lay in complex capital goods, such as aircraft, electrical machinery, generators, and medical and scientific equipment. “From 2004 to 2011, U.S. imports of Chinese advanced technology products grew by 16.5 percent on an annualized basis, while U.S. exports of those products to China grew by only 11 percent.6 In August 2011, U.S. exports of advanced technology products to China stood at $1.9 billion, while Chinese exports of advanced technology products to the United States reached $10.9 billion, setting a record one-month deficit of more than $9 billion. On a monthly basis, the United States now imports more than 560 percent more advanced technology products from China than it exports to that country.

U. S. Exports to and Imports from China of Advanced Technology Products in the Month of June ($ billion) 2004-2011  Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Trade in Goods and Services (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, August 15, 2011).

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Trade in Goods and Services (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, August 15, 2011).

The Commission states that “the weakness in U.S. exports of advanced technology products to China is explained in part by barriers to market access experienced by U.S. companies attempting to sell into the Chinese market.” Import barriers are part of China’s policy of switching from imports to domestically produced goods. China’s policy of ‘‘indigenous innovation’’ protects domestically produced goods by discriminating against imports in the government procurement process, particularly at the provincial and local levels of government.

Seventy-one percent of American businesses in China believe that foreign businesses are subject to more onerous licensing procedures than Chinese businesses according to a recent survey conducted by the American Chamber of Commerce in China. A similar 2011 study by the European Chamber of Commerce in China found that inconsistencies in the procurement process employed by the Chinese central government resulted in a lost opportunity for European businesses that is equal in size to the entire economy of South Korea, or one trillion dollars.

China’s Role in the WTO

Since the last Report, the U. S. brought three new, China-related disputes to the WTO. “On December 22, 2010, the United States requested consultations with China over its subsidies for domestic manufacturers of wind power equipment (DS419). The European Union (EU) and Japan joined the consultations in January. The case has not yet advanced to the hearing stage. In the second case, the U. S. requested consultations with China regarding its imposition of antidumping duties on chickens imported from the United States. In addition, on October 6, 2011, the U.S. Trade Representative submitted information to the WTO identifying nearly 200 subsidies that China, in contravention of WTO rules, failed to notify to the WTO. Three previous WTO cases involving U.S.-China trade are both open and active. The Raw Materials case, which resulted in a decision favorable to the United States, is under appeal as of August 31, 2011. The Flat-rolled Electrical Steel case and the Electronic Payments case have both advanced to formal dispute settlement, though no decision has been reached…The United States has brought a total of seven cases against China at the WTO concerning subsidies or grants. Of the seven, four were settled through consultation, two were decided in favor of the United States, and one remains undecided.”

China’s WTO Probationary Period Ends This Year

During the 15 years of negotiations leading up to China’s accession, the United States and the European Union expressed concern about potential negative consequences that might befall the WTO due to China’s sheer size and lack of a market-based economy and they insisted on a series of China-specific admission requirements. “The centerpiece of this ‘WTO–Plus’ admission package was the Transitional Review Mechanism, which required China to submit to an annual review for the first eight years of its membership in the organization, as well as a final review in the tenth year. The Transitional Review Mechanism is in addition to, rather than in lieu of, the normal review procedure, known as the Trade Policy Review Mechanism that all WTO members must undergo every few years in perpetuity.”

The temporary Transitional Review Mechanism appeared to be more stringent than the Trade Policy Review Mechanism. “However, the procedural aspects of the Transitional Review Mechanism rendered it a paper tiger. Reports produced by the Transitional Review Mechanism require the unanimous consensus of all members involved, including China. This puts China in the position of acting as judge in its own trial,” so that the result consistently has been ‘‘light and generally unspecific criticism,” according to trade scholars such as William Steinberg.

The Transitional Review Mechanism provided the United States with a somewhat useful tool for fact-finding and focusing attention on controversies within the U.S.-China trade relationship, but this is the final year of the Transitional Review Mechanism as China’s tenth year of WTO membership. The consequences of this are:

- The tools available to the United States to carry out fact-finding related to China’s compliance with WTO obligations will now be limited to the Trade Policy Review Mechanism and the various review channels of individual subsidiary bodies.

- China’s membership in the WTO has reached a point of chronological maturity at which China was expected to be in full compliance with its WTO obligations.

China initially “accepted the China-specific rules contained in the protocol of accession, avoided litigation within the WTO, and was quick to comply with all demands of the WTO’s dispute resolution process.” But after ten years of observing and learning the subtleties of WTO procedural law, “Beijing has become much more aggressive about bringing claims against trading partners, appealing decisions that are rendered against its favor, and pushing the envelope of noncompliance. Additionally, China has grown very savvy about using the dispute settlement process and bilateral free trade agreements to undermine the effectiveness of China-specific rules.”

According to a recent study by international trade law scholars at the University of Hong Kong, of the five WTO cases filed by China between September 2008 and March 2011, four of them were designed to use the dispute settlement process to change or undo rules contained in China’s Accession Protocol and purposely focused on the vague terminology found in the Protocol.

China has exploited the vague terminology by using creative interpretations to render entire provisions inapplicable. “Since 2002, China has concluded nine free trade agreements and commenced negotiations for five more. In all 14, a precondition to negotiation has been agreement by the other party to grant China market economy status. These preconditions are targeted toward eliminating certain restrictions placed upon China during accession to the WTO,” particularly, “the one in which the instituting party is allowed to use price comparisons from third-party countries in order to show dumping behavior by Chinese companies” when antidumping proceedings are instituted against China.

Also, for purposes of identifying illegal subsidies and calculating countervailing measures, “the instituting party may act with reference to prices and conditions prevailing in third-party countries in lieu of China.” However, under the terms of the Accession Protocol, “China’s nonmarket-economy status is set to expire in 2016, at which time these provisions will cease to have effect.”

However, “the expiration in 2016 of China’s status as a nonmarket economy under the Accession Protocol does not negate applicable U.S. domestic law, which will continue to have effect beyond 2016. If enough WTO members accord market economy status prematurely to China, it will diminish support for Washington’s position that China has a long way to go to merit market economy status. China has more bargaining power in bilateral negotiations with smaller nations than it does in multilateral negotiations at the WTO.” The Commission concluded that “China hopes gradually to undermine the Washington consensus, strong-arm its way into market economy status, and shake free of restrictive terms and obligations in its accession agreement” by pushing for concessions from a series of bilateral negotiations under the auspices of free trade agreements. In addition, “China is not willing to comply fully with the decisions of the WTO dispute settlement process and prioritizes the preservation of its own political system above fidelity to WTO commitments.”

Implications for the United States

The Report states, “The U.S. trade deficit with China has ballooned to account for more than half of the total U.S. trade deficit with the world and creates a drag on future growth of the U.S. economy. This problem has many causes, among which are barriers to U.S. exports and continued undervaluation of the RMB. The result is lost U.S. jobs. While the exact number of U.S. jobs lost to China trade is hotly disputed—economist C. Fred Bergsten has estimated 600,000 jobs on the low end, while the Economic Policy Institute has estimated 2.4 million jobs on the high end—many parties agree that the costs are staggering.”

While the Chinese RMB has appreciated by roughly six percent over the course of the last year, there is widespread agreement that it remains deeply undervalued (30-40 percent according to some economists). As a result, “U.S. exports to China remain subject to a de facto tariff, Chinese exports to the United States remain artificially discounted, and Chinese household consumption remains suppressed. The Report states this “contributes to a persistent pattern of massive and dangerous trade distortions, unnatural pools of capital, and dangerous inflationary pressures that threaten the stability of the global economy.” China is no longer content to be the low-end factory of the world ? the government is intent on moving up the value chain into the realm of advanced technology products, high-end research and development, and next generation production at the expense of America’s high-technology industries. The Commission opines that “it no longer seems inconceivable that the RMB could mount a challenge to the dollar, perhaps within the next five to ten years. Chinese financial authorities are laying the groundwork for these ambitions via a series of bilateral arrangements with foreign companies and financial centers.”

The U. S. and the EU went to considerable lengths during the 15-year negotiation process “to design and negotiate a system of checks and balances that would permit China to accede to the WTO without jeopardizing the smooth functioning of the organization or endangering the position of existing members in the international trading system.” In less than ten years, “China has learned the nuances of WTO law and has begun to use it systematically to undo the finely wrought balance that U.S. and EU negotiators designed. At the same time, China has shown that it will subordinate its international commitments to its domestic political preferences and deny to its trading partners the benefit of their bargain.”

This chapter concludes with the comment, “China has grown more assertive and creative in using WTO procedures to alleviate, eliminate, and avoid certain restrictions in the Accession Protocol. At the same time, the WTO has ruled that China’s existing system of state monopoly over imports of cultural products is inconsistent with WTO obligations. China has not yet complied fully with the WTO ruling, and the United States has the right to initiate further proceedings to compel China to do so.” This is an understatement to say the least.

Has President Obama or his staff read any of the last three reports? Has any Congressional rep, Senator, or their staffs ever read through any of the Commission’s reports during the past ten years? If they did, why didn’t they insist on the Bush administration and now the Obama administration initiating proceedings to compel China to comply with their WTO obligations? Why didn’t our government do anything about China’s currency manipulation, product “dumping,” and subsidies to State-owned enterprises before they destroyed many of our domestic industries? Why is China’s ten year probationary period concluding without anybody doing anything to prevent their becoming a full member of the WTO? Why hasn’t the news media asked any of these questions of our elected officials? Americans have been betrayed by their leaders, and we need to hold them accountable. Every candidate for president and President Obama better read this latest report and tell the American people what they intend to do to address China’s threat to our economy and national security. The question is whether the news media will have the courage to ask these hard questions during the campaign for president. The future of the United States as a sovereign nation is at stake.